If you were like me, Philosophy 101 hit you with a mind-boggler: different theories of truth.

But here’s a secret: there’s no such thing.

There’s no “theory of truth” like there’s a “string theory” or “broken windows theory” because truth isn’t theoretical: it’s not a studied hypothesis or even a body of thought. To be meaningful at all, “truth” must mean its dictionary meaning: “the body of real things, events, and facts”.[1]

Many things aren’t real and many things may or may not be real. But one thing we know is real is that some things are real—in other words, that truth exists. That’s because any contrary statement (e.g., “nothing is real” or “truth does not exist”) is itself a statement of reality, or truth claim—and therefore self-contradictory, and therefore false. At least something must be real, even if it’s the reality that many other things aren’t. Therefore truth itself simply can’t be a theory; it must be a fact.

Truth also must be fact, not opinion or experience in the sense of “my truth” and “your truth"

Truth also must be fact, not opinion or experience in the sense of “my truth” and “your truth,” lest facts still exist and the word “truth” simply cease describing them. Then we’d have to throw “truth” into the bin of other relative words like “perspective” and “story” and find some new word for the absolute concept.

But the real question in “theories of truth” is how that absolute concept “truth” works. What makes something true? Is it correspondence with some external fact? Coherence with current knowledge? Working pragmatically?

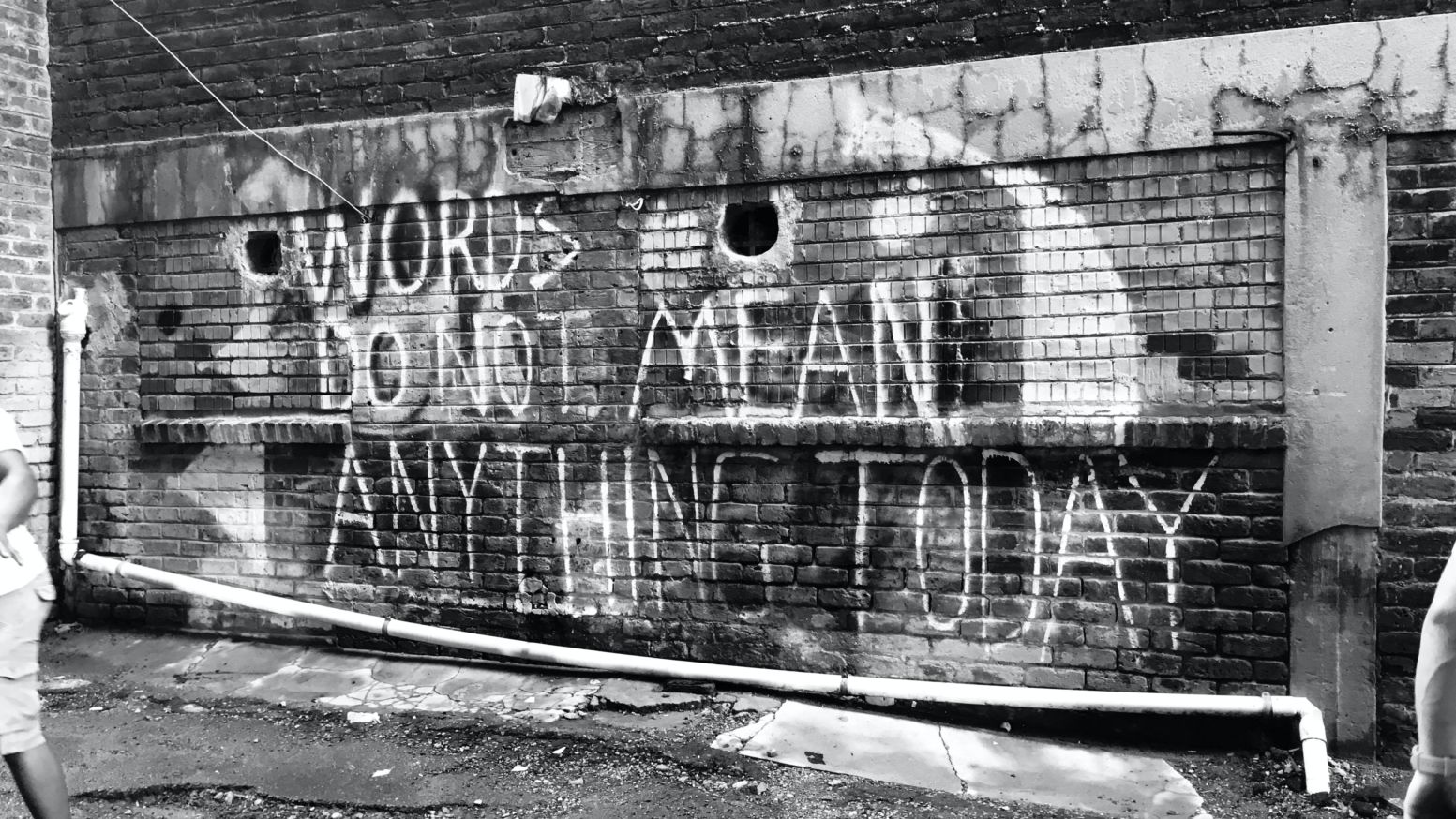

The problem with proposing different truth theories is that however noble or intellectual the intentions, it shrouds in wordplay truth’s only meaningful definition: fact. Truth is fact whether or not it’s ever known, believed, liked, or agreed upon. Truth is fact--it is objective and attainable. And the fact is, no philosophy can talk facts away.

[1] “Truth.” Def. 1. Merriam-Webster.com, Merriam Webster, www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/truth. Accessed 2 June 2020.