As noted in our previous blog, The Euthyphro as it is called asks the following questions: Is something good because God wills it? Or, does God will it because it is good? There is more to these seemingly innocuous questions than one might first realize. These questions, in fact, form a strong dilemma. Plato asks the DCT adherent which he believes:

- God’s commands are arbitrary (from the first question).

- Good is external to God (from the second question).

Which will the DCT adherent affirm? He cannot affirm both. And, at first assessment, it is hard to see how there could be any alternative to choosing one. To defend the viability of DCT, one must answer the Euthyphro.

In truth, however, regardless of which proposition the DCT adherent affirms, in the eyes of the secular ethicist, he would be grasping the fatal nettle. Each horn of the dilemma is equally dangerous for DCT. On the one hand, if the DCT adherent affirms (1), he commits DCT to the untenable position that God’s commands are simply arbitrary. This permits the reductio ad absurdum critique that God could command anything, rape, murder, cruelty, etc., and it would be morally justified. This surely cannot be correct. So, the DCT adherent must reject (1). But, he cannot affirm (2) either. For, to affirm (2) would be to hold that what is good is determined by something outside of God. But, if good is determined by something outside of God, then God is not necessary for grounding or knowing good. This, however, is a contradiction of the central thesis of DCT and must be rejected. So, it seems there is no good option for the DCT adherent.

If it is supposed that the Euthyphro succeeds, the secular ethicists might make a strong case for following certain overarching moral principles which are shared among virtually all religions and all cultures. For example, even if Matthew 7:12 did not enjoin the Golden Rule upon man, humans could agree amongst themselves to do unto each other as they would have each other do to them. Or, forsaking Bibles and other sacred texts, secular ethicists could still appeal to human life as a source for values and duties, etc. In this way, secular ethicists claim they could establish a secular ethics that united people in their commonly held morals and carefully avoided conflicting sources of moral authority in the particulars. For this reason, many secular ethicists from Hume to Russell to Dawkins to Rachels[1] have argued for just such a new secular moral system.

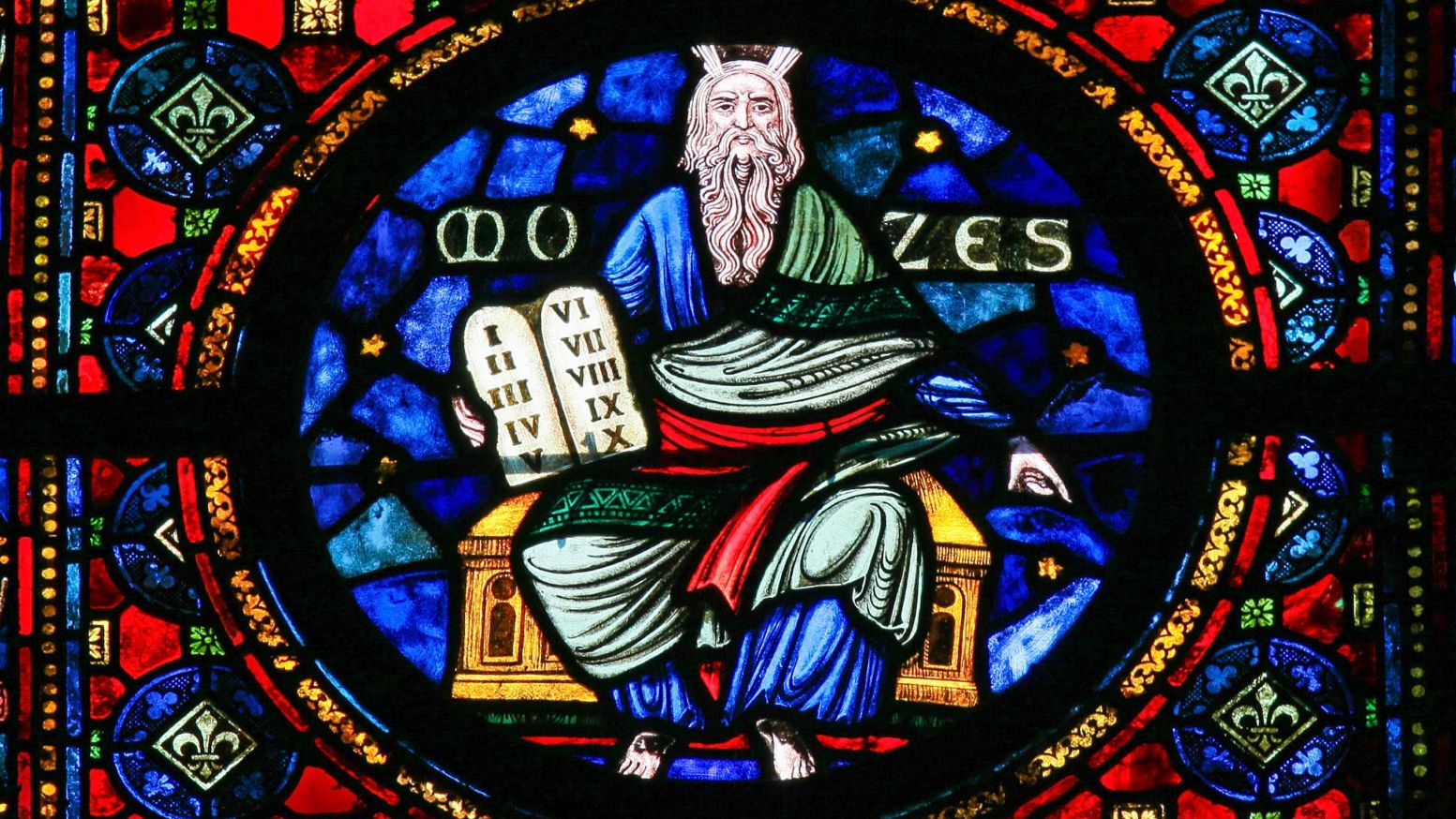

To conclude the discussion here by conceding defeat to the Euthyphro, however, would be to ignore another possibility. There is a strong case to be made that the Euthyphro, for all its cleverness, is really just a false dilemma. The likes of Augustine, Aquinas, and Anselm have all rejected the dilemma in favor of retaining DCT. But, on what basis can the dilemma be rejected? The answer: there is a third way. This tertio modo is reasoned as follows: God is the source and definition of good. As the Psalmist says, “The Lord is good” (Psalm 100:5). His commands are good because they flow from and reflect his perfectly good nature.[2] In this case, it is argued that God’s commands are not simply arbitrary. Instead, they are objectively good because they correspond to and are issued from God’s perfectly good nature. Also, good is not external to God. Rather, it is grounded in God’s perfectly good nature. As such, whether God’s will is knowable or not (a separate question), God’s will could still possibly be a perfect moral law.

So, what should be made of DCT in light of the Euthyphro? It may be a bit too early yet to throw DCT out. Surely, it is at least logically possible that DCT could be the proper description of the real moral law as we Christians believe it is. Taken in combination with other reasons, many people, including me, feel confident to affirm Divine Command Theory as a viable theory and the correct theory of ethics.

Divine Command Theory, if true, provides something we desperately need: a source for gounding objective moral values and duties. If God's perfectly good nature is the source of moral values and duties, then we have an objective standard in reality by which to establish right and wrong. If God's perfectly good nature is not this much-needed grounding, it seems that no such grounding exists. So, the DCT adherent might respond to the Euthyphro by asking if God is not the source of moral values and duties, who or what is? A fair question indeed for the opponent of Divine Command Theory!

[1] Pojman, Louis P., and James Fieser. Ethics: Discovering Right and Wrong. CengageLearning, 2017, pp. 200-205.

[2] Moreland, J. P.; Craig, William Lane. Philosophical Foundations for a Christian Worldview (Kindle Location 14809). InterVarsity Press. Kindle Edition.